I wondered, weeks ago, why chapter three was named for Libo instead of Novinha, and now we have the answer: Card was saving her name for this chapter. Chapter three, of course, was the chapter in which Novinha ruined science, came up with like four terrible plans to protect her boyfriend, and then called Ender to save the day. Presumably now, twenty-two years later, she'll have a much better showing, right? (Just kidding; ya'll know how he do.)

(

Content: domestic abuse, and if anyone can think of how the hell to summarise Ender's deal in this chapter, please make a suggestion, because it's terrifying. Fun content: scientists who dare to follow the scientific method, those bastards.)

Speaker for the Dead: p. 123--133

Chapter Eight: Dona Ivanova

The notes this week are from Libo again, and again an excerpt from evidence used in some future trial, and also hilarious, because it turns out that the xenologers have been intentionally giving the Little Ones new knowledge since Pipo was still alive. I almost want to call this a retcon, except I can't off-hand think of any 'Oh no we revealed things' moments that chronologically came after the acrobat incident. Anyway, Libo is explaining to his daughter how much lying she'll have to do in her reporting as well, to avoid revealing the Prime-Directive-breaking to the other scientists:

When you watch them struggle with a question, knowing that you have the information that could easily resolve their dilemma; when you see them come very near the truth and then for lack of your information retreat from their correct conclusions and return to error--you would not be human if it didn't cause you great anguish.

(Remember, species is decided by vote.) The one thing I like about this is how much withholding information from other scientists is cast as the exact mirror of withholding it from the Little Ones, which is the least-condescending thing that the book has yet done for them. I mean, given Card's characterisation of Other Scientists, it's still no compliment, but it's a step up from "What's the deal with all of the not-raping?"

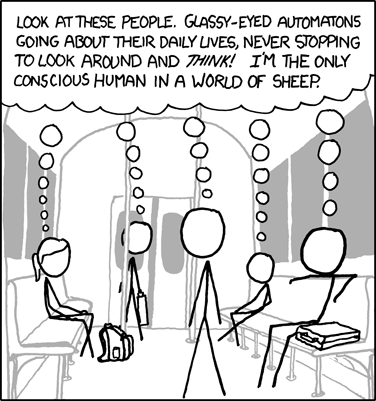

And for every framling scientist who is longing for the truth, there are ten petty-minded descabeçados [headless ones] who despise knowledge, who never think of an original hypothesis, whose only labor is to prey on the writings of the true scientists in order to catch tiny errors or contradictions or lapses in method.

Like,

fuck peer-reviewers, am I right? 'Rigour', pah. 'Reproducible results', double-pfeh! Science isn't about constantly re-checking and re-testing and investigating apparent contradictions in order to smelt through masses of data in order to identify the common and reliable truths of the processes of the universe! Science is about

writing things down.

And let's not forget that these xenologers on other worlds have zero ability to actually test any of their hypotheses; if they study Little Ones, literally the

only thing they can do all day is re-read the reports of the xenologers of Lusitania and try to link facts together in new ways. Once they've come up with an

"original hypothesis", the only way they can test it is by checking whether it matches all existing data, and asking the Lusitanians to find a way to test it more directly. They're all detectives who are never allowed to leave their desks, and Libo is criticising them for

noticing contradictions.

Given that Card is not and has never been a scientist, and given how logic-free some of his writing has proven to be, it's hard not to read this more as an attack on critics of art (as compared to those great creators, the authors) than on insufficiently-creative scientists.

But maybe the best part is

what information Pipo and Libo started sharing:

That means you can't even mention a piggy whose name is derived from cultural contamination: "Cups" would tell them that we have taught them rudimentary pottery-making. "Calendar" and "Reaper" are obvious. And God himself couldn't save us if they learned Arrow's name.

Yup. That's how that's gone down. Pipo and Libo, xenologer academics, have taught the Little Ones pottery, archery, farming, and time-keeping. And they think it's a much better and safer idea to keep these things quiet rather than indicate that the Little Ones might have invented any of these things themselves. In a society built mostly of secrets and places humans aren't allowed to go, they figured

never mentioning that they had given the Little Ones calendars was easier than saying "Oh, and they must be trusting us more because today I overheard one of them talking about a holy day coming up and they've revealed they do in fact have a calendar after all!"

But more to the point:

WHY. The Little Ones are low-tech, but they also have no need to be otherwise. They have no predators and they don't hunt large animals, so they have no use for archery except war--did Pipo and Libo learn/teach how to make bows so they could defend themselves better against the other tribes? (What if the close-contact murder is actually vital to the genetic exchange in their wars? It would be awful but also kind of perfect if they gave the Little Ones bows and arrows for combat and the entire species died out in ten years because they were killing in a non-reproductive manner. Card would have to be on board with that; we know how he feels about non-reproductive genetic exchange.)

The Little Ones also don't have any reason to farm that we know of, so why reaping? Agricultural revolutions completely reshape societies if they take effect at all. And wouldn't the satellites notice if the Little Ones started farming and were able to support a much larger population? We don't even understand their current nutritional needs and yet they adopted farming and yet they haven't done anything with it in twenty years?

This book is an amazing exercise guide for critical thinking skills.

Novinha is finishing up in her lab at the end of the day, stalling before going home, chastising herself for not being a better parent, never seeing her youngest children except when they're asleep in bed. She thinks she should be happy Marcão is gone, thinks that

"all our reasons expired four years" ago, and wonders why she never thought of leaving him, even if they couldn't get divorced. She's still aching from the final time he beat her, three weeks ago.

The pain in her hip flared even as she thought of it. She nodded in satisfaction. It's no more than I deserve, and I'll be sorry when it heals.

So, Novinha is obviously horrifically emotionally and mentally damaged, in ways that are pretty normal for abuse survivors: she's internalised the idea that she deserved to be hurt (she keeps using the phrase

"no worse than I deserve"), even though she hated him. I wait to see whether she gets corrected or if Card determines that she really did 'deserve' to be hurt for her sins. As she approaches her home (having bid a rather poetic good-bye to her plants), she sees all the lights are on and grows immediately suspicious.

Olhado is uploading/downloading memories when she arrives, and she thinks a bit about the ones she wishes she could delete and could replace, and how it's her fault, her curse, that Olhado lost his eyes instead of being

"the best, the healthiest, the wholest of my children", which I hope will be explained because: what? Olhado tells her that the Speaker has arrived, and she panics as Ela shows up with cafezinhos in the kitchen. Olhado and Ela try to tell their mother that Ender is italicised-

"good", unlike what the bishop claimed, but she takes silent pride in being unshakable, and reflects on how it's not her fault Libo is dead, since she kept her secret all those years. She sits, and Ender, still a ninja, reaches in and is already pouring before she notices him.

"Desculpa-me,"she whispered. Forgive me. "Trouxe o senhor tantos quilômetros--"

"We don't measure starflight in kilometers, Dona Ivanova. We measure it in years." His words were an accusation, but his voice spoke of wistfulness, even forgiveness, even consolation. I could be seduced by that voice. That voice is a liar.

Look, y'all, I'm doing my best, but I cannot speak and I can barely imagine how to turn those two sentences into an accusation

while expressing wistfulness

but allowing for forgiveness

and offering consolation. Like, two,

maybe, and I would sound like a twit to anyone except maybe someone very emotionally damaged who was just happy I wasn't brimming with evil.

Novinha apologises for having called him away twenty-two years, and Ender just says he hasn't noticed it yet,

then he springs the passive-aggression on the abuse victim he's supposedly come to help:

"For me it was only a week ago that I left my sister. She was the only kin of mine left alive. Her daughter wasn't born yet, and now she's probably through with college, married, perhaps with children of her own. I'll never know her. But I know your children, Dona Ivanova." [....]

"In only a few hours you think you know them?"

"Better than you do, Dona Ivanova."

Everyone gasps, though Novinha privately thinks he might be right, but more importantly how does

Ender judge this? He knows literally nothing about Dona Ivanova; he invented a bond with little Novinha and then arrived here and learned nothing about the family before coming to see them. He has literally no evidence on which to judge how well she understands her children. He then turns to walk out, and Novinha snaps at him to come back, but he proceeds to her bedroom, where Miro and Quim are arguing. Novinha is startled to see Miro smiling, but it vanishes when he sees her, which stings more. She tries to ignore it and tell Ender again to leave, saying he has no death to speak, saying that as a foolish girl she imagined the original Speaker would come and console her.

"Dona Ivanova," he said, "how could you read the Hive Queen and the Hegemon and imagine that its author could bring comfort?"

It was Miro who answered [....] "the original Speaker for the Dead wrote the tale of the hive queen with deep compassion."

The Speaker smiled sadly. "But he wasn't writing to the buggers, was he? He was writing to humankind, who still celebrated the destruction of the buggers as a great victory. He wrote cruelly, to turn their pride to regret, their joy to grief."

Just a note: first the mayor wasn't shocked Ender could be two thousand years old, and now Novinha suggests that the Speaker might have lived three thousand years, and yet literally no one except Plikt (who needed

four years to entertain the notion) actually considers how far into ancient times people might have come forward in this galaxy. Speaking of scientists who lack creative thought and curiosity.

I do like this exchange as far as it can be taken as a commentary on scripture, and the changing meanings of old writing, the way people might look at something today and see a story completely different from the way it might have struck its original audience. Again, a very weird thing to hear from the keyboard of Orson Scott Card, given that he's the worst kind of fundamentalist and bigot.

Novinha mentions the Speaker's target, Ender, a person who ruined everything he touched, and Ender snaps for a moment,

"his voice whipped out like a grass-saw, ragged and cruel", to say that everyone touches something kindly and to say a person destroyed everything they touched is

"a lie that can't truthfully be said of any human being who ever lived", and I am abruptly and uncomfortably aware that Marcos is going to get a post-mortem redemption arc.

Ender says that while Novinha called him first, others have called speakers since then, so it's not all on her conscience, and she wonders who else could know enough about speakers to have done so. She's shocked to learn someone called a speaker for Marcos, that anyone would miss him, and Miro speaks up:

"Grego would, for one. The Speaker showed us what we should have known--that the boy is grieving for his father and thinks we all hate him--"

"Cheap psychology," she snapped. "We have therapists of our own, and they aren't worth much either."

Wait, they

do have therapists? No. Not buying it. The last time we saw anyone with anything approaching therapeutic qualifications they were Valentine's school guidance counsellor. The planet

should have therapists, among many other things, but I just don't believe for a moment that Card's universe contains therapists. At some point, someone would go to one.

Miro and Ela start laughing about Grego soaking Ender's pants, and Novinha has a montage of flashbacks, the joy of Miro and Ela as small children, Marcos' slow growing hatred, the way everything was ruined by the time Quim was born and he never got a happy childhood. Marcos' rage grew

"because he knew none of it belonged to him", foreshadow, clunk. Novinha's response to this flash of cheer is of course to retreat to rage that anyone would interrupt the quiet gloom she's created, and try to throw Ender out again, though she knows the law protects his quest for TRUUUUUUTHHHHH.

"If I told nothing but what everyone already knows--that he hated his children and beat his wife and raged drunkenly from bar to bar until the constables sent him home--then I would not cause pain, would I? I'd cause a great deal of satisfaction, because everyone would be reassured that their view of him was correct all along. He was scum, and so it was all right that they treated him like scum. [....] No one's life is nothing. Even the most evil of men and women, if you understand their hearts, had some generous act that redeems them, at least a little, from their sins."

There's some back and forth about whether Novinha is really hating Marcos or herself, how recently Ender studied her younger self, how Pipo loved her, et cetera, but I'd rather focus on the above. There is this cultural notion we have with empathising with the worst people. Empathising with good people is obvious and admirable, but empathising with villains is the mark of A Great Heart. You may notice that in that dichotomy, no one ever gets around to empathising with the middle ground. The neutrals, the people who are just trying to get on with their day, they're not part of the consideration. You have to be a hero or a monster before anyone cares about anyone caring.

So let me provide an advance alternative interpretation--I'm guessing it's alternative, I'm guessing this isn't what Ender is going to say, although if I'm wrong about that I will be 1) impressed and 2) irritated that my blog hasn't won the Nebula and Hugo awards.

Marcos' truth is the story of no one stopping him. Marcos is an abuser and apparently everyone knows and no one has ever done a thing to intervene. They know that he beats Novinha, but the police don't stop him, they know that Grego is practically feral but they don't help him, they don't try to draw Novinha--daughter of Os Venerados, sole master of shaping and reshaping life for their alien world, bringer of potato vodka--out of her abusive home and into a shelter, or haul Marcos out of his house and into a jail cell. They do have cops, apparently, cops who will kick him out of the bars but not stop him from nearly murdering his wife. And for two decades they have watched him grow more terrible and violent and watched him damage his family and they have done nothing, because it was easier to pretend everything was okay. It's the same gross neglect that they inflicted on Novinha until she became xenobiologists, but extended four times as long and harming five or six children instead of one. How's that for a truth that would make the people of Milagre uncomfortable and shake their assurances that they did the right thing by gossiping about how awful Marcos was?

But yeah, I can't

wait to hear Ender explain that Marcos' had a secret kindness that redeems him.

Novinha tries again to throw Ender out of the house and yells at him in Portuguese, and we get another grammar lesson about how rude she was with her pronoun forms, and yet Ender's response in the same overly-familiar Portuguese tones was instead kind and intimate:

"Thou art fertile ground, and I will plant a garden in thee". Wait, what? He walked into her house, got all her children on his side, told her that she's too cruel to herself and to the memory of her abusive husband, and then told her he would

plant a garden in her fertile ground?! That is the creepiest fucking thing I have read in months.

Oh, and then Quara wakes up crying and Novinha hears Ender go into her room and soothe her with a Nordic lullaby. Forget it. This is just a straight-up horror flick now. Next morning he's going to be wearing Marcos' skin like a snuggie.

Novinha falls asleep, and when she wakes again in the night she hears her children gathered in the living room, Miro and Ela and Quim and Olhado, laughing together, and she dreams that Libo is among them, alive, her true husband, foreshadow, clunk. She fears that Ender will, in repairing her family, learn her secrets and reveal them and Miro will die like Libo did, because apparently she's in denial that keeping her secret didn't protect him. I'm not clear if Ender ever actually left the house or if he just moved in. Regardless, that's the merciful end of this chapter. Next week: science investigation, Ender is a jackwagon, and in a shocking twist teenage xenologers make bad decisions.